Do We Really Need SSTO If We Have Full Reusability?

Where Are My Spaceships?

Comics of the 1950s promised silver bullets softly touching down on colorful alien worlds, piloted by dashing men of derring-do. They were explorers’ vessels, roving untethered from planet to planet in a single piece: True spaceships in every sense.

Having just set an all-time record for global launch attempts, we’re closer to being a spacefaring species than ever before, but our rockets look nothing like what we were promised. Why do our rockets break apart? Wouldn’t it be easier to reuse them if we built proper single-stage spaceships?

The Holy Grail of Rocketry

The dream of reusable rockets dates back to the early space age. Throwing away a perfectly good rocket after one flight was just as bizarre to early aerospace visionaries as it was to Elon Musk. Flyback boosters, helicopter retrieval of the Saturn V first stage… These and several other possibilities were all explored by twentieth century engineers.

But they firmly believed that the true holy grail of reusability was a single-stage-to-orbit (SSTO) rocket, and it’s easy to see why. A single-stage craft is the simplest possible architecture; no staging nonsense, and only one part to refurbish.

Insufficiently advanced materials technology prevented Earth-bound SSTO vehicles from being seriously pursued for decades, until the 1990s, when NASA was seeking a more advanced replacement for the Space Shuttle. Presenting…

The Only Serious SSTO: VentureStar!

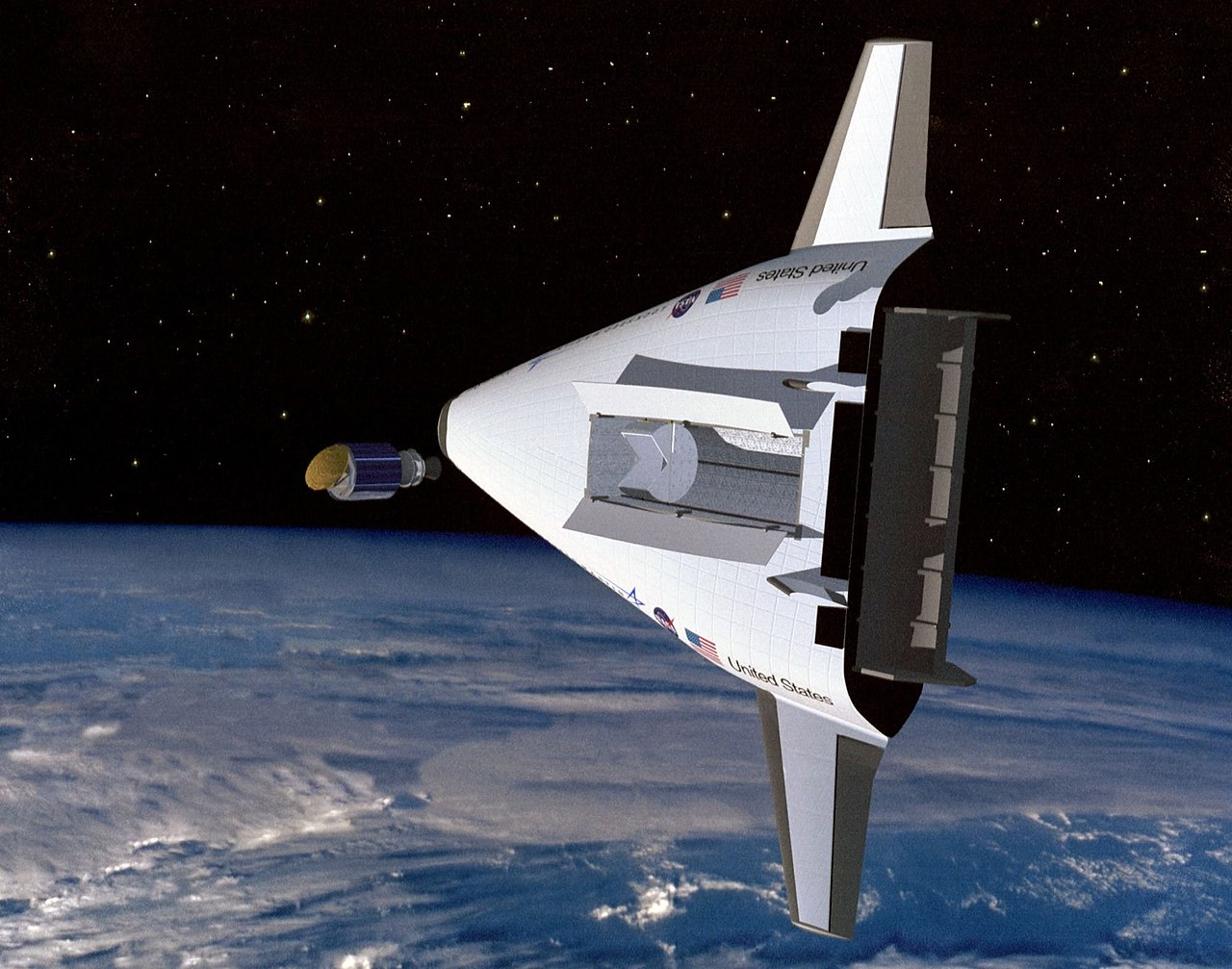

VentureStar, also known by its smaller test craft, the X-33, was a seriously funded design to create a VTHL (vertical takeoff, horizontal landing) SSTO spacecraft.

It checked all NASA’s boxes: Reusable. Single-stage. Crewed. It also promised to extend Shuttle’s impressive heritage, turning “refurbishable” into “reusable” with metallic heat shield tiles. In a boon for engine enthusiasts, it also made use of the XRS-2200 linear aerospike for propulsion, promising efficiency at all altitudes. So why aren’t we living in a spacefaring paradise?

As it happens, humanity had overstepped its technical prowess, again. During a high-profile test of a lightweight composite tank, the test article suffered a catastrophic failure. With the now-decried composite technology considered a vital component of the design, this set the stage for the program to be canceled in 2001.

The fact that VentureStar’s viability rested on a next-generation, ultra-lightweight composite tank brings us to the crux of the issue with SSTOs: their dismal mass margins.

The Tyranny of the Rocket Equation

A rocket’s chief job is to accelerate useful mass to eye-watering speeds at dizzying heights. Low-earth-orbit velocity is around 7.2 kilometers per second, but the average rocket requires closer to 9.3 km/s to get there, accounting for ascent and gravity losses.

Using Konstantin Tsiolkovsky’s rocket equation, i.e. that the potential change in velocity (delta-V) is equal to the specific impulse of the engine multiplied by standard gravity, again multiplied by the natural logarithm of wet mass over dry mass, we can determine exactly how much of an SSTO vehicle must be fuel.

Assuming a desired 9.3 km/s to reach orbit, and a specific impulse of 450 seconds (higher than the sea-level performance of any extant first-stage engine currently in operation), we can calculate that we would need 822 kg of fuel to send 100 kg of mass to orbit.

This mass fraction is quite reasonable with modern materials technology, and Tory Bruno, former CEO of ULA (heir to the VentureStar project), remarked that the project’s composites issues had since been solved:

So why did SSTO lose the market to multi-stage craft? Let’s run our analysis again, but assume that of our rocket’s 100 kg dry mass, 60 kg of it is hardware left on the first stage. If our first stage achieves 3 km/s and the second achieves an additional 6.3 km/s, we only need 364 kg of fuel - a savings of over 50%!

Contrived? Perhaps. The key point is that despite requiring extra mass for staged engines, multi-stage craft can discard the unnecessary mass of an entire stage once its propellant is spent. This makes them far more fuel-efficient, and is the main reason why every orbital rocket to date has been staged.

Finale: Multi-Stage and Reusability

The most lauded benefit of SSTO vehicles remains unaddressed: Their capacity for reusability. It stands to logic that a single stage is easier to reuse than two or more.

Currently, reusability is restricted to first stages such as the Falcon 9 and New Glenn boosters, which need not traverse the inferno of orbital reentry. Upper-stage reusability eludes all but the Space Shuttle, not counting Commercial Crew and the Gemini SC-2 capsule.

However, upper-stage reusability is fundamentally the same problem as SSTO reusability. The difference is that the multi-stage mass margins work in our favor, allowing us to pack in more recovery equipment or heatshields. The economics of multi-stage don’t change when reusability is introduced. If anything, they make the case stronger.

Humanity may someday build a single-stage-to-orbit craft, but the business case doesn’t make it likely anytime soon.

Bonus: The Manhole Cover

“But wait!” the space nerds are shouting, “humanity has launched a single-stage-to-orbit craft!”

They’re talking about Operation Plumbbob, which merits special mention at the end of our journey.

Picture this: It’s the 1950s, and nuclear testing fervor is at a radioactive pitch. The United States is curious about the behavior of underground detonations, and conceives a cunning plan to test their potency. They lower a nuclear bomb into a dazzlingly deep hole, and securely weld a one-ton steel lid onto the top. Just for kicks, they point a high-speed camera at the welded “manhole cover”.

The spectacularly powerful blast barely even notices the welded cap, and shoots it clear into the sky. The camera only caught the manhole cover in the air for a single frame, leading researchers to estimate its speed at six times Earth’s escape velocity.

Unfortunately, scientists agree the manhole cover was probably vaporized by the atmosphere almost instantly, and humanity has yet to reach orbit on a single stage. Unless, of course, you count the Apollo Lunar Module Ascent Stage!

0 Comments